When the six students in Rice University lecturer Divya Chaudhry’s first-year Hindi course began their semester, they could never have imagined they’d find themselves routinely chatting with high school students in New Delhi, nor that in a few months’ time they’d have created a video campaign that would be shown in government-run schools across India.

Students in a New Delhi high school video chatted with Rice students throughout the semester in Divya Chaudhry’s first-year Hindi course.

Modern technology, especially high-speed internet, has drastically changed the way foreign languages can be taught at the university level — not to mention the positive outcomes that result from out-of-the-box approaches to language acquisition.

A motivated professor who values adaptation and flexibility makes all the difference, too.

“For the longest time, one of the things I really wanted to do is find a reason for students to learn the language that goes beyond the classroom,” said Chaudhry, a Delhi native who has spent years researching linguistics and second-language pedagogy.

What you learn beyond the classroom, she said, is the sort of cultural context that can’t be artificially constructed, such as why young children are often addressed with the most formal pronouns in Hindi or why Tupperware is seen as an aspirational product in many Indian households. The long-term benefits go far beyond the primary goal of learning another language.

Ahead of her second-semester course for Hindi language students, Chaudhry began searching online for nongovernmental organizations working in India, motivated by the instinct that a partnership between a university and an India-based NGO would produce a uniquely immersive experience for both her students and the NGO.

Chaudhry was introduced to Yuva Unstoppable through Palak Jalan, whom she met on an Indian mentorship group on Facebook. Jalan had been the program director for healthcare initiatives for Yuva Unstoppable in the Indian city of Ahmedabad for four years before she moved to Houston for graduate school.

Yuva — which means “youth” in Hindi — has become India’s largest organization working to improve education and facilities in government-run schools. What began in 2005 as a volunteer effort is now a global operation working with over 950 Indian public schools, upgrading restrooms and water fountains and installing technology in classrooms for the very first time.

Chaudhry (second from right) met up with Yuva Unstoppable team members Taranjeet Kaur, Ruhbani Singh and Rishi Singh when she visited Delhi.

“This is a very unique thing that we are doing in India,” said Rishi Singh, head of strategy and communication for Delhi-based Yuva. Soon, Singh and Chaudhry were brainstorming about how that new technology could be used for a joint project between Yuva and Rice.

In the past three years, Yuva’s upgrades to 180 of its public-school partners have included the addition of laptops and Google “smart classrooms” that host online educational environments. These allow Indian students and teachers to collaborate with higher education partners across the world, Singh said, including Harvard, Columbia and Yale.

Just this month, Amitabh Shah, who founded Yuva as a 23-year-old, received an International Ellis Island Medal of Honor for the work the NGO has done in India by partnering with international educational and corporate organizations.

“But with Rice we did a great experiment,” Singh said. “This we never did with anybody.”

‘This very, very small thing was very inspiring’

The great experiment was video-chatting in Hindi with the 10th grade students in a Delhi high school. The video chats quickly morphed into a video pen pal format after everyone realized how difficult it was to coordinate classroom sessions when it’s 10 a.m. in Houston and 8:30 p.m. in Delhi. The students found value in both formats, which emphasized an immersive and conversational approach.

So talking with the Yuva students challenged us to be, in a sense, immersed in ‘real’ Hindi conversation,” said Rice senior Meredith Church, shown on screen.

Rice has native Hindi language tutors, said Hanszen College senior Meredith Church, who took both of Chaudhry’s first-year courses.

“But they also speak English and are there to help us as tutors, whereas we were really trying to get to know and form relationships with the kids in India by way of speaking Hindi with them,” said Church, who’s majoring in linguistics and Spanish and Latin American studies. “They also speak Hindi quickly and naturally, whereas teachers and tutors generally attempt less of a conversational pace so that we can understand more easily. So talking with the Yuva students challenged us to be, in a sense, immersed in ‘real’ Hindi conversation.”

Church appreciated that the video pen pal format allowed her and her Rice cohort to consider what they wanted to communicate ahead of time, then shoot multiple takes of their videos to catch and correct errors before they were sent.

“The videos we sent them allowed us to polish our Hindi a little more,” she said.

And when they were able to fit in live chats, the students found they had more to discuss.

“It was really touching to see how excited the kids were to chat with us in Hindi,” Church said. “They talked with us about things we’d mentioned in our videos from our personal lives and things like Bollywood movies, which is a subject of particular interest to me.”

Rice students used the Hindi they’d learned in their first semester to immerse Indian students in their world, recording video of everything from their friends and family to their messy dorm rooms and their dinners in West Servery. Some even sent footage of themselves playing cricket on a sunny Houston day and sledding down a snow-covered hill over a weekend break.

“Here in India, the students totally enjoyed it,” Singh said. “The best part was that we never thought that students from any foreign institute would like to interact with the students in Hindi.”

Soon, the students were sending more and more of these videos back and forth. The Rice students became more deeply immersed in Delhi culture while the Indian students, most of whom had never left their city before, were able to interact with young people on the other side of the world.

“I loved interacting with Rice University students,” said 10th grade student Binita Lakra. “They talked with us in Hindi and they are very nice. They also made a video on plastic awareness which we liked the most. I want to talk to them again.”

The teachers and volunteers in the school were buoyed by the interactions, too.

“I can’t explain how much happiness (Rice) has brought to students in the government schools,” said Taranjeet Kaur, who helped coordinated the video chats with fellow Yuva volunteer Ruhbani Singh. “This is totally an unforgettable experience for these kids in our school. This interaction has given a new dream and hope to these students for learning in a foreign university in future.”

“These kids here in common schools, they’ve never had any kind of live interaction — neither have they seen some kind of interaction video — with foreign students,” Singh said. “This very, very small thing was very inspiring. This was an amazing beginning.”

But Chaudhry wasn’t done.

‘A beautiful memory for life’

Halfway through the semester, Chaudhry went home to Delhi on personal business. She met up with Singh, and the two devised another innovative way of adapting technology to further the cross-cultural camaraderie they’d seen develop in just two short months.

Yuva was conducting sessions in government schools on harmful effects of plastics and Singh wondered if Rice students could talk to the kids on the subject. When she returned to Houston, Chaudhry told her students about their final project addressing Yuva’s needs: Create a short video and flyer to be shown in Yuva schools educating Indian students against the use of plastics.

A massive source of pollution in India, 26,000 tons of plastic waste is generated within the country every day, 40% of which ends up littering rivers, choking drainage systems and polluting its oceans.

This wasn’t as much of a problem, Chaudhry explained, before plastic containers such as Tupperware became aspirational consumer products, supplanting traditional food vessels such as steel thalis and dabbas. A solution would require a similarly nuanced understanding of Indian culture.

Students began preparing for the campaign through reflecting on their past experiences and an analysis of existing Hindi advertisements. They concluded, said Chaudhry, that “effective campaigns have a story that touches your heart”. So the students wove a narrative of a young girl who misses her departed mother and looks for ways to honor her memory. The young girl also misses Mother Nature, Chaudhry said, “and she wants therefore to do things for her. It’s such beautiful, powerful imagery.”

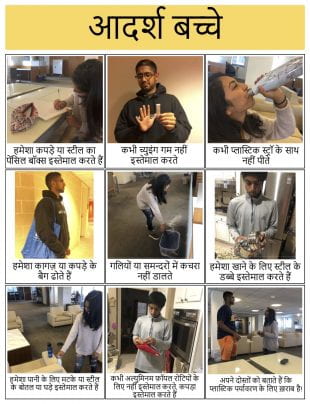

The students also created a poster based on a popular educational aid of the past: “adarsh balak,” or the ideal boy.

The ideal boy posters focused on the teaching of “good” habits and development of children’s reading skills, with such examples as, “The ideal boy gets up early in the morning and salutes the parents and also does very random stuff like, ‘He brings lost kids to police station,’” Chaudhry said.

The ideal children in this plastic campaign flyer created by the Rice students use a tiffin, or steel lunch box, and jute instead of plastic bags. The use of “children” instead of ‘boy’, was another intentional choice to make the poster more inclusive.

“It’s not just that you’re coming up with an idea, what is important is that you’re thinking of what is relevant for the Indian context,” Chaudhry said.

Rice students often had to video chat with the students in Delhi at odd hours to catch them in their classroom.

All of this came together around a project no one had planned for. “It was a plastic campaign that we could have created in class, but for who?,” Chaudhry said. “Because it had a real audience and it had a real purpose, that made all the difference to how Rice students engaged in the project.”

The intentionally ad hoc basis on which the final project was created was meant to mirror the world after college in which being presented with new and unexpected tasks is a given — yet another life skill imparted by this unconventional course.

“I am somebody who likes to know what’s going to happen; I like certainty,” Chaudhry said. “So I had to prepare myself and the students that this semester-long engagement with Yuva Unstoppable is not going to be structured. There are going to be things that we didn’t plan for and you have to be comfortable with uncertainty and you have to be able to change things on the fly. And the students surpassed those expectations”

Learning the daily realities of life in India was also crucial to the project, said Church, who credited those regular interactions with the Yuva students and volunteers and Chaudhry for providing additional cultural context throughout the course.

“I really cannot emphasize enough how excellent of a teacher Divya-ji is,” said Church, who added the honorific suffix “ji” when discussing Chaudhry. “As a part of the course, we also had to attend a certain number of cultural events outside of class, like a Diwali celebration in the fall semester, cooking sessions to learn how to make Indian street foods, Bollywood movie watch parties, etc. — and these helped enormously in our having a more holistic understanding of not just the Hindi-speaking world but the entire nation of India and its many diverse cultures.

“I’m definitely amazed at the depth of cultural knowledge I’ve acquired in only two semesters of Hindi with Divya-ji, but I attribute all of it to her exceptional teaching prowess,” said Church. She was even able to keep up with the class online once she left for Cusco, Peru, on a study abroad program — further expanding the world presented to the Indian students during each video communique.

The Indian students were equally inspired by their interactions, Singh said, with many reporting that the live chats and pen pal videos provided encouragement to learn English, travel internationally and attend college just like their new pen pals at Rice.

“We feel so connected with Rice, and we would especially love to have this kind of interaction every year,” said Singh, who hopes to continue partnering with Rice students on future projects through Yuva. “This was a great experiment, a wonderful experience and a beautiful memory for life.”