Rice-made memory chips make it to ISS aboard groundbreaking cargo mission

The journey of a set of devices from Rice University to the International Space Station (ISS) earlier this month gave new meaning to the concept of “fast chips.”

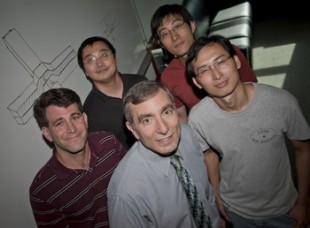

Members of the team that invented the first silicon oxide memory, a version of which was sent into space this month, are, clockwise from left, Rice Professors Doug Natelson and Lin Zhong, former graduate students Zhengzong Sun and Jun Yao, and Professor James Tour. Photo by Jeff Fitlow

Rice sent its unique silicon oxide memory chips to the ISS as part of a NASA experiment to test their ability to hold a pattern when exposed to radiation in space.

The chips got there in a hurry aboard a Russian supply mission, Progress 48. Usually ships carrying people or supplies take two to four days to catch up with the ISS. But the mission that launched Aug. 1 promised same-day delivery – a first. The trip from launch to docking took less than six hours. (See the launch here and the docking here.)

“It’s exciting to see years of our research tested in the real environment where it might one day be used,” said James Tour, the T.T. and W.F. Chao Chair in Chemistry as well as a professor of mechanical engineering and materials science and of computer science. “That the science has reached this level is a joy for our entire team.”

Postdoctoral associate Jian Lin, graduate student Adam Lauchner and former Rice graduate student Jun Yao developed the chip in the labs of Yao’s advisers — Tour; Douglas Natelson, a professor of physics and astronomy and of electrical and computer engineering; and Lin Zhong, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering.

Silicon nanowire forms when charge is pumped through silicon oxide, creating a two-terminal resistive switch. Graphic by Jun Yao/Rice University

The nonvolatile memory chips are part of an experiment called HiMassSEE; a container of devices from various sources will spend two years aboard the station to test for radiation hardening. At the end, they will be returned to their labs for comparison with identical chips stored on Earth to see how primary and secondary ionizing radiation affected their circuitry.

The technology behind the chips was a breakthrough when announced two years ago — a story that landed on the front page of the New York Times. Yao discovered that bits of memory could be embedded into slices of insulating silicon oxide by applying a charge to electrodes on either side. The jolt stripped the oxygen atoms and left behind five-nanometer channels of pure silicon – a conductor. Lesser charges would break and reconnect the silicon repeatedly and make a two-terminal memory unit.

The first attempt to send samples to the ISS was less successful. On Aug. 24, 2011, the day Yao left Rice for a postdoctoral position at Harvard, HiMassSee launched from Kazakhstan on Progress 44, a cargo mission that crashed minutes later in Siberia. Russian investigators found the cause was a malfunction in the Soyuz rocket’s third-stage engine.

Steven Koontz, the ISS system manager for space environments in charge of HiMassSee, said at the time in an email to his research partners that nearly all the materials needed for a duplicate payload were in place. “As Winston Churchill is reported to have said (many times), ‘Never ever, ever, ever, ever quit,'” he wrote.

Two-terminal memory chips made of silicon, one of the most abundant materials on the planet, could lead to very dense memories for computers and other electronics. The chips may become a key element of transparent electronics, and help extend the limits of miniaturization subject to Moore’s Law.

Dr. Tour and the staff at Rice University continue to be leaders in the field of research in nano technology that will have a profound positive impact the world for years to come. Keep up the great work.